Heat stress can take a toll on dairy calves, impacting feed intake, growth and health. Learn how using data from an automatic calf feeder can help detect heat stressed calves.

CALVES FEELING THE HEAT?

Leverage your autofeeder system to detect and abate calves feeling heat stress.

*This article is contributed by Dr. Bethany Dado-Senn, Vita Plus Corporation, and Dr. Jimena Laporta, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Dado-Senn is a Calf and Heifer Technical Specialist with Vita Plus and was a former Ph.D. student under Dr. Laporta. Their combined research interest pertains to hyperthermia in dairy youngstock, particularly the consequences of prenatal heat stress on early-life calf performance and heat abatement strategies for pre-weaned dairy calves. References available upon request.

Compared to mature dairy cows, dairy calves are not typically considered for heat abatement because they are more thermotolerant as essentially nonruminant and nonlactating animals. However, youngstock are still susceptible to heat stress and, depending on the duration and severity of heat load, can experience:

- Increased panting, sweating, and core body temperature

- Decreased dry matter intake

- Reduced average daily gains and weaning weights

- Weakened immune response and poorer health outcomes

On-farm, it can be difficult to monitor some of these responses day-to-day. Further, current heat abatement strategies for calves are minimal, focusing primarily on shading or ventilating individual calf hutches. However, capitalizing on features of group-housing and autofeeder data collection can allow for early detection and intervention of heat stress in your dairy calves. The following suggestions come from a series of studies conducted by the Laporta research group at the University of Florida, investigating heat stress versus active cooling in group-housed, autofeeder managed calves.

Heat stress detection

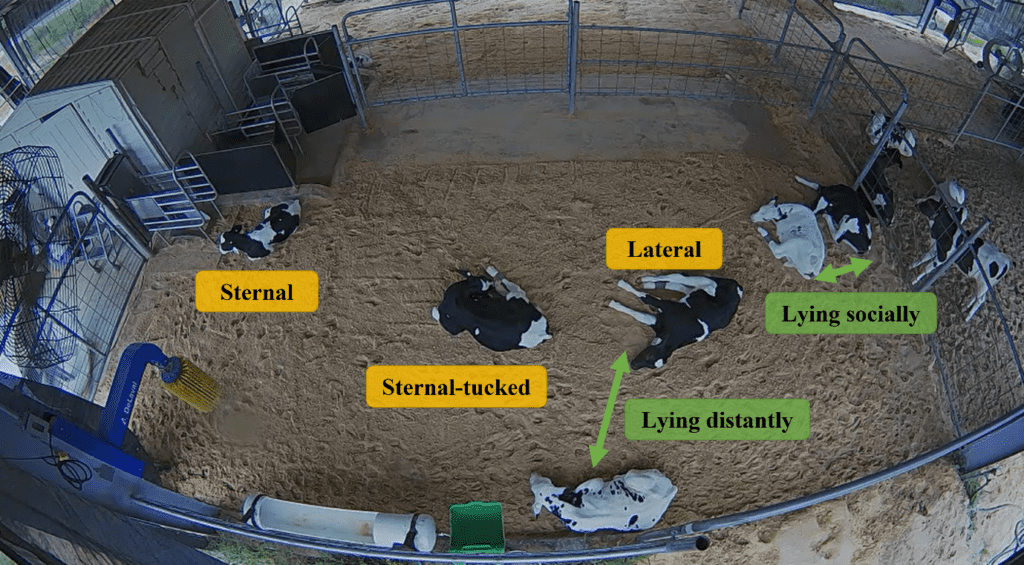

Basic monitoring of calf behavior can give you ample insight into general calf discomfort and potential heat stress. Group-housed calves under heat stress may have increased standing time or display thermoregulatory behaviors like lying in “lateral” postures, lying further from pen mates, or lying near areas of greater air movement to dissipate heat.

Additionally, you can actively observe calf behavior responses, a task that is relatively straightforward in shaded, group-housing scenarios.

- Simply counting flank movements (i.e., respiratory frequency) for a subset of calves is a low-cost, non-invasive option.

- Our research group also recommends using infrared thermometers to detect rises in skin temperature on the calf rump, another low-cost, non-invasive and time-effective option.

- Though more time-intensive and invasive, assessing calf core body temperature using a rectal thermometer remains the gold standard for heat stress detection in calves.

- Initial heat stress threshold detection finds that an abrupt increase in these behavior responses will occur around 65 to 70oF (18 to 21˚C) or a temperature-humidity index between 65 to 69 in a subtropical climate. These environmental benchmarks correspond to respiration rates between 35 to 40 breaths per minute, skin temperatures around 73oF (23˚C), and rectal temperatures around 101.6oF (38.7˚C).

Finally, there is also extensive data that can be leveraged from your autofeeder to detect calf-side heat stress. Relative to calves provided active cooling, calves under chronic heat-stress conditions:

- Consume less milk replacer under a step-up/step-down ad libitum feeding program

- Visit the autofeeder the same number of times but eat less milk per visit, leading to an overall increase in rewarded visits

- Consume less starter grain concentrate prior to and up through weaning

While initial heat stress benchmarks for behavioral responses are at a much lower THI, the surrounding environment reaches a much higher threshold, around a THI of 82 (or ambient temperature of ~86oF (30˚C), before a significant decrease in dry matter intake is realized. This suggests that productive losses under elevated ambient temperatures may not occur unless there is severe heat stress, but actions should still be taken at those lower environmental benchmarks to prevent these more serious consequences and promote proper calf comfort and welfare.

Heat stress prevention

So, you’ve identified signs of heat stress in your autofeeder-managed calves – now what? Well, a distinct advantage of the auto-feeder system is that calves are group-housed and indoors, allowing for more strategic heat stress abatement. For instance, some of the most optimal heat stress abatement strategies identified in hutch-housed calves – supplemental shade and proper ventilation – are more-or-less inherent to group-housed calves.

Therefore, the next frontier of calf heat reduction is the consideration of more intensive forms of heat stress abatement such as leveraging curtains, positive pressure tubing, or even fans to further promote active ventilation as a form of heat mitigation.

There is very little research assessing the impacts of mechanical ventilation on calf performance under heat stress. One study in indoor, individually housed calves in Ohio found some benefit of fan provision on lowering respiration rates and improving average daily gains, though there was no impact on concentrate intake.

In contrast, our studies in Florida have found that employing calf- and ceiling-level fans in group-housed pens greatly improves air speeds, calf behavior responses, and dry matter intake but did not translate into improvements in body weight or stature growth.

However, there were some additional benefits related to calf immune response and medication events that might still justify the usage of fans to promote calf comfort and productivity. We are hopeful that there will be more work done in this area to target best-practices for fan usage and determine long-lasting benefit of cooling on heifer growth and future milk production.

In summary, initial detection of heat stress in pre-weaned dairy calves can include monitoring calf-side behavior, as well as assessing intakes via the automatic feeder. The basis of group-housing for autofeeder managed calves provides an excellent framework for the provision of more rigorous forms of heat stress abatement to maintain calf thermal comfort and prevent reductions in feed intake and growth. If you have a question about monitoring heat stress calves with autofeeders ask it in the comment box.